Monday, July 23, 2012

"The Dark Knight Rises" Review

Thursday, March 22, 2012

"The Hunger Games" Review

Superfans be easy. If your barometer for measuring the success of Hollywood's Hunger Games adaptation begins and ends with faithfulness to the source material, by all accounts it is one. If you can swing a bit of emotional transference, all the better — I suspect few who enter without a preexisting love for Katniss and Peeta will be moved by their exploits. This $78 million companion piece to Suzanne Collins' young adult novel isn't especially concerned with converting the uninitiated; it's about cashing in on a fertile franchise. Cha-ching!

For the rest of you: Katniss Everdeen is a girl from District 12. In the future, America is divided into 12 districts under a totalitarian government. Once a year, at a grim lottery known as a "reaping," two adolescents' names are drawn to represent each district in a televised battle to the death known as The Hunger Games. Katniss, 16, has survived several reapings, but when her younger sister's name is called, she volunteers to fight in her stead.

Directed by 55-year-old Gary Ross, The Hunger Games isn't exactly brimming with angst and youthful energy. His craftsmanship is competent, but Ross puts too much pressure on the talent to sell Collins' world and contributes too little himself. Where's the scale? The novel pops with aesthetic opportunity, but Ross isn't visionary enough to really capture our imagination. District 12 is a destitute mining community that counts starvation and black lung among the leading causes of death. Show us that. By skimping on act one atmosphere, the director undermines the comparative splendor of the bizarre and extravagant capitol city.

Ross routinely sabotages the emotional potential of Collins' story and setting. The reaping in particular lacks narrative punch. Ross adequately animates the flesh of the scene, but as a storyteller he fails to find the soul. On paper, a family is splintered and an act of defiant bravery instigates a Herculean trial. Ross puts the impetus on the audience to feel the weight of that choice — artistically, he renders the scene with all the gravitas of mild indigestion.

And the cast — talented though its constituents may be — often feels curiously misplaced. Kudos to Ross for casting an anti A-lister like Jennifer Lawrence as his lead, but he negates any goodwill with clunky misallocations of more famous folk. Woody Harrelson sticks out like a sore thumb as drunkard slash mentor (in that order) Haymitch Abernathy. Harrelson's half-hearted take on the character plays like a spacey stoner from a bad SNL sketch. Stanley Tucci and Lenny Kravitz are also underwhelming as Hunger Games host Caesar Flickerman and stylist Cinna, respectively.

It feels like an eternity before the games actually get underway, and it quickly becomes apparent (this is a criticism consistent with the novel) that any illusion of challenging the preconceptions of preteen storytelling disintegrates. Granted, there's a bloody death or two, but mostly Katniss gets by with clever alternatives to direct combat — there's something distinctly Home Alone-ian about watching her drop a hornets' nest onto her would-be assassins. For Ross' part, he frames the action just inelegantly enough to obscure any offensive violence.

Ultimately, what works about Hollywood's Hunger Games adaptation are the traits intrinsic to the novel. A worthy premise lends a compelling backdrop to a young adult coming-of-age sci-fi romance whatchamacallit — and Ross borrows those ideas wholesale. It's all there. His is a relatively faithful transcription of the source material, and it's a shame he does so little to distinguish his version. He fails to replicate the emotional oomph of Collins' imperfect novel, and expands upon those imperfections with lazy visuals and uneven pacing. After all, when financial success is a certainty, there's little incentive for a director to think outside the box.

Naturally, my complaints will carry little weight with the Hunger Games superfans, for whom this film was expensively and exclusively realized. If you count yourself among that elite group — read no further. This is your film. Enjoy it.

3/5

Friday, February 3, 2012

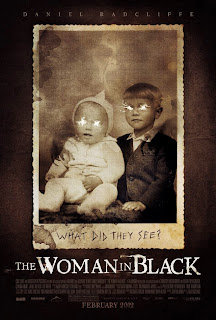

"The Woman in Black" Review

Recipe for a Hollywood horror flick: pick a screenplay with a vaguely creepy-sounding title like The Woman in Black. Be sure the writer included one or all of the following: portraits with the eyes scratched out, little kids' drawings, antique toys, etc. Next, shoot everything at half exposure. Then pick a quiet weekend to release and collect your fifty million dollars. Repeat. It's a racket that works like a charm, and isn't going away until the audience does.

The Woman in Black stars 'Arry Potter 'imself — Daniel Radcliffe — as Arthur Kipps, an adolescent English estate lawyer bound unluckily for a haunted house in the boondocks. Kipps' job is on the line, which accounts for his eager beaver attitude upon arrival, and dogged insistence on seeing the property, even against the behest of, oh, everyone in town. You know where this is going.

Once inside the isolated island manor, Kipps can’t seem to get any work done. A typical sequence of scenes plays out with the protagonist sitting down to study a stack of documents and being immediately distracted by some foreign sound or supernatural happening. And then the investigation's afoot; jump scares abound, though they fall too formulaically to conjure much anxiety or subsequent shock. After all, scares by appointment aren't very scary.

The screenplay is particularly disappointing given its author, Jane Golden, who spun genre into gold with Kick-Ass and X-Men: First Class. Too dour to pass as a throwback haunted house flick, and too clichéd to surprise anyone, The Woman in Black is caught in the nebulous nowhere between fun and frightening. Even if her writing were stronger, however, there's no guarantee it would be spared the blunt hand of James Watkins, a director with the finesse of a steamroller.

He brings not an ounce of aesthetic originality to the table, imbuing the movie with the same ugly, washed-out palette of six dozen other studio horror failures. The technique is intended to foster a mood, but it's a cheap substitute for good old-fashioned filmmaking. Mood isn't achieved in camera — it's an aggregate of art direction, camera placement, performance, music, etc. The obvious digital look of the film also hampers the believability of its period setting — the turn of the century never looked so bland.

Performances add little life to the landscape. Daniel Radcliffe manages not to embarrass himself, and that's being generous. Frankly, it's tough to buy the Hogwarts alum as a dad when he's been playing a teenager for ten years. It's equally tough to imagine him a widower, as he broods with all the emotional turmoil of an Olsen twin. Ciarán Hinds plays Kipps' sole confidant in the haunted hamlet, and fittingly enough, delivers the film's sole compelling performance. Still, his character never goes anywhere, a waste of Hinds' talent.

Effective horror is contingent upon a willingness to take the audience outside its comfort zone, and The Woman in Black is too creakily formulaic to creep us out. Because Hollywood is a business, it's more desirable to greenlight a derivative script and hire a yes-man director than to risk something edgier that might not pay off. The cycle continues. The Woman in Black follows that recipe to a T, but there's something lost in translation. Maybe the recipe wasn't all that good to begin with. Maybe the whole cookbook needs to go.

2/5

Thursday, January 26, 2012

"The Grey" Review

So it's come to this: Liam Neeson, a pack of wolves, and a filmmaker with delusions of grandeur. The Grey might have passed as merely a second-rate survival flick had it laid off the pseudo-intellectual grandstanding and quickened the glacial pace. Unfortunately, its shepherd, Joe Carnahan, knows no such restraint. Bloated, juvenile, and absurd, the movie attempts to pass off a few cheap thrills as an ode to humanity. Oh, and according to Carnahan, it may return to theaters to make an Oscar run in October. Give me a break.

Neeson plays Ottway, a professional wolf hunter with a penchant for internally reciting corny poems written by his deceased daddy. "Once more into the fray/ Into the last good fight I'll ever know/ To live and die on this day," he rasps. Hey, how that's poetry elective going? It might seem profound as a beer hall anthem to rally spirits in the fourth quarter, but it's embarrassingly maudlin as the emotional crux of a movie. But enough about poetry — let's talk about wolves.

A plane crash strands about half a dozen men in The Middle of Nowhere, Alaska. Hounded by a pack of edgy predators, the crew must literally fight for their survival. Never mind the practical how-tos like sustaining an expedition without potable water — they've got man-hungry wolves on their tail! The biggest, nastiest wolves special effects can conjure, though they're mostly relegated to chasing everyone from one tired setpiece to the next.

Here's the problem — with riveting wilderness docs like Touching the Void and Encounters at the End of the World streaming online, there's no excuse to settle for such a stagey drama. But Werner Herzog is obviously beyond these morons; someone in The Grey paraphrases Grizzly Man as that movie about "The fag and the bears." Are these guys from Alaska or a college fraternity?

I don't demand that any character be likeable — but I ask that they be interesting. Not a one in Ottway's ragtag group of "fugitives, drifters, and assholes" brings a single compelling trait to the table. Ottway wins the likability contest by default, even though his character might as well be the Wikipedia page on wolves for all he contributes to the conversation.

And it's a shame we're stuck with such shallow people, because their trek is often atmospheric, and the many perils they face might mean something if we actually cared about who they are. Writer/director Joe Carnahan can get by on keen visuals, but he writes like an emotionally stunted 19-year-old. His ceaselessly abrasive, hollow characters engage in dialogue with all the wisdom and wit of a whirring garbage disposal. Their pointless, profanity-laden bickering and eventual, manufactured camaraderie play stilted, not uplifting. Just die already.

The Grey is a mangy, flea-bitten excuse for an epic with an obnoxiously inflated self-image. Nowhere in its unwarranted 117 minutes does it possess a shred of the intellectuality it pompously aspires to, nor does it achieve a badass nirvana despite its consistent, cocksure projection of masculinity. Carnahan succeeds in scoring a few cheap thrills, but he ought to leave the philosophizing to the artists. End rant.

2/5

Sunday, January 22, 2012

"Haywire Review"

Haywire is a lot like last year's Drive. What both lack in substance, they make up for in style. Likewise, both could be dismissed as pulp dreck if their respective directors hadn't classed up the material. Haywire isn't as riveting as last year's sleeper hit, but the way Steven Soderbergh stages and choreographs the action elevates it from generic genre fare; especially apparent in contrast to its opening weekend competition: Underworld Awakening.

Punctuated by terse life-or-death scuffles between a badass black ops agent and her would-be assassins, it's no wonder Soderbergh hired martial artist slash actress Gina Carano (not to be confused with Carla Gugino). Of her handful of big screen credits, Haywire is by far the biggest deal; her casting is a move reminiscent of another recent Soderbergh flick — The Girlfriend Experience, which marked the dramatic debut of porn star Sasha Grey.

Both actresses fit well in the roles Soderbergh picks for them, but I question how well either would come off when working with a director less versed in coaching non-actors. Perhaps the most impressive thing about Carano's performance is that she holds her own in such formidable company: Ewan McGregor, Michael Fassbender, Michael Douglas, Bill Paxton, Antonio Banderas, etc. Channing Tatum. The list goes on.

Their collective effort is in large part what makes Haywire such a breezy watch. 93 minutes soaking wet, the film flashes backwards and forwards in its narrative to keep the momentum from faltering (and also, I reckon, to gussy up a simplistic espionage tale). The IMDB synopsis says it all: "A black ops super soldier seeks payback after she is betrayed during a mission." The film's final moment perfectly reflects the entirety: cheesy, cheeky, fun, and ultimately, forgettable.

Famous for his Hollywood haggling to get passion projects off the ground ("One for me, one for you"), Soderbergh is blurring the line between his studio pictures and personal films. With Haywire, the lack of marketing oomph and no-name lead suggest it might fall into the "One for me" category, especially after his crowd-pleasing Contagion. But if the audience I saw it with was any indication, Haywire is no less accessible.

Nor does it feel as obligatory as, say, an Oceans sequel. For the most part, Soderbergh brings his A-game, although I do take issue with the cheapo aesthetic. The harsh digital look he seems fond of works in low-key experiments like Bubble, but feels out of place in a fast-paced action flick. Dim, bland interiors with overblown light sources lend to the film's overall disposable vibe.

But while it lasts, Haywire is an enjoyable January actioner. Though it pales in comparison to Nicolas Winding Refn's excellent Drive, they have a lot in common: a bare bones story spearheaded by a brutal and ruthless protagonist, and a director who knows how to play them to maximum effect. Drive skews operatic while Haywire skews goofy, but both provide more compelling action sequences than any of last summer's blockbusters, Contagion included.

Plus, this time of year empirically means slim pickins for the discerning cinephile. It's either this or Underworld, folks. I'll give you a minute.

3/5

Friday, December 9, 2011

"Shame" Review

Sex without the pleasure — and you thought starving to death in an Irish prison was rough. Following Hunger, director Steve McQueen's new collaboration with Michael Fassbender is a similarly self-destructive character study. Shame stars the latter as Brandon Sullivan, a sex-addicted New York businessman whose explicit lifestyle is threatened by the surprise arrival of his orphaned sister (Carey Mulligan). Loaded with full-frontal male and female nudity and graphic depictions of sex, the NC-17 rated flick may not be coming to a theater near you.

Far from crass or exploitative, however, McQueen's film succeeds in making Brandon's many lascivious liaisons feel obligatory rather than erotic. Shame is Requiem for a Dream for sex. A gorgeously shot but emotionally upending orgy late in the film drives home the utter desperation of the act in a prolonged close up on Brandon's contorted face. Excited yet?

McQueen's flirted with minimalism before. Smack dab in the middle of Hunger is a seventeen and a half minute static shot in which Fassbender's character dialogues with a priest. While it showcases two terrific performances, such laissez-faire filmmaking techniques do little for me. Shame likewise features long, deliberate takes, but McQueen's evolution as a director is apparent from his dynamic use of the frame.

For example, during a dinner date between Brandon and his coworker (Nicole Beharie), a subtle camera push-in (from the wide restaurant interior, bustling with the comings and goings of patrons and waiters, to an intimate two shot) keeps the emphasis on the performances without needlessly drawing attention to the process. It's the rare circumstance where more is actually less. Conversely, the extreme close up of Carey Mulligan's face when she performs a heart-wrenching rendition of "New York, New York" works because she fills the entire frame. By comparison, the aforementioned sequence in Hunger is visually flabby, full of superfluous space.

But Shame isn't just a technical triumph — even more compelling is what's in the abstract. Fassbender's alluringly enigmatic portrayal of his volatile character is the centerpiece of a complex, cerebral story. Brandon carries his addiction like a ticking time bomb in his breast pocket, and things get particularly uncomfortable with his vulnerable (and oddly familiar) sister around. Their relationship adds a grimy layer of squeamish tension to the film.

Unhappiness manifests itself in many shapes in Shame, from Brandon's insatiable carnal appetite to the loneliness of the women in his life. Incapable of transcending their physical connections, the characters share sex or blood, but don't understand each other or strive to communicate better. The result is intercourse that frequently comes across dehydrating, disgusting, or dehumanizing. Sometimes all three!

Shame isn't without its moments of levity. McQueen's subtle humor saves him from slipping into the mire of downbeat melodrama. James Badge Dale plays Brandon's wingman (or is it the other way around?), whose paper-thin personality and repeated drunken strikeouts never fail to conjure a smirk. Also, I'm not sure there's a world where getting caught masturbating isn't at least a little funny. But leave it to Steve McQueen and Michael Fassbender to make it captivating too.

The culmination of lesser successes, Shame sees both actor and director at their best. Fassbender makes Brandon's incongruities flesh (so to speak), and McQueen strikes the perfect balance between minimalistic staging and cinematic artistry. Shame is an ambitious, ambiguous film that ranks easily among the year's best. Plus, you get to see Michael Fassbender naked. There's also that.

4/5

Tuesday, December 6, 2011

"Hugo" Review

Who's the audience for Hugo? With roots in the fantasy/adventure genres and a comfortable color palette for the Harry Potter and Twilight crowds, "preteen" seems a safe bet. But it undergoes a metamorphosis around the midpoint that fixed my posture and put the kids to bed. Not that I'm complaining.

The two halves of Hugo are at odds. In the first hour, we meet Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield – the spitting image of a prepubescent Malcolm MacDowell), an orphan and wee tinkerer living behind the walls of a Parisian train station circa 1930. He lives only to wind the clocks and scavenge parts for his prized automaton – a wrecked robot with sentimental ties to his late father (Jude Law). A chance encounter with a young girl (Chloë Moretz) may be the key to unlocking the secret of his antiquated android.

In the second, Scorsese taps his inner film buff. Enter French silent filmmaker Georges Méliès, whose spectacular oddball A Trip to the Moon features prominently. Hugo posthumously honors the artist's underappreciated oeuvre, complete with stunning recreations of his avant-garde genre flicks. The also-underrated Michael Stuhlbarg plays film historian Rene Tabard, a champion of Méliès' lost legacy.

Somehow, the story of a boy and his robot and the redemption of a brilliant, misunderstood artist mesh, if reluctantly. I can't feign complete enthusiasm for Hugo's by-the-numbers fantasy beginning, but loved the playful manipulation of art history it preceded. Conversely, I imagine the general audience will go for the "Once Upon A Time," but neither know nor care who Méliès is. Some may walk away none the wiser to the elements of nonfiction.

Unifying Hugo's disparate halves are gorgeous storybook visuals bolstered by inspired use of 3D tech. Action sequences up the gee-whiz factor, but Scorsese's most compelling use of the gimmick is also among his most subtle; touches like adding the effect to Méliès' films has the revelatory effect of making history come alive. And it doesn't carry the stink of desperation that accompanies Disney and Star Wars' conversions. As a magician who embraced every trick in the book, Méliès would have loved 3D.

Another constant is the caliber of the performances. The principals are solid, and Hugo is packed with veteran character actors who breathe vibrant life into their world. Folks like Ray Winstone as Hugo's Drunken Uncle, Ben Kingsley as a shopkeeper with a secret, Christopher Lee as a kindhearted librarian, and Sacha Baron Cohen as the bumbling station inspector help even the one-dimensional roles shine.

Pushing himself while pushing 70, you have to admire Scorsese's dogged tenacity. The director won his long-belated Best Director Oscar in 2007 for The Departed, which seems to have freed him from falling into an Eastwood-esque downward spiral; first with the psychological thriller Shutter Island, and now with the unabashed fantasy, Hugo. That jarring juxtaposition is just one factor in obfuscating who its audience is supposed to be.

Diplomatically, the new Martin Scorsese picture aims to please everyone, but divides more than it unites. Parents may be left twiddling their thumbs during the first drama-lite hour, and kids may nod off during the second half history lesson. However, for a particular breed of cinephile, Hugo is magic – a love letter to film from a master of the medium. Scorsese's adoration is tangible – not for Georges Méliès specifically – but for artists both great and small. It's sublime. It's beautiful. But bring a pillow.

3.5/5